Το Nauru Project είναι ένα συνεχές, διαδικτυακό, συνεργασιακό project με θέμα το νησί Ναουρού, το υπο-πτώχευση μικρότερο νησί-κράτος στον κόσμο. Με βάση το blog (www.nauruproject.blogspot.com), το project περιλαμβάνει την ερασιτεχνική συλλογή και ανταλλαγή ποικίλων πληροφοριών γύρω απο το νησί Nαουρού, καθώς και την παραγωγή καλλιτεχνικού έργου με βάση τα σχετικά ευρήματα.

Φιλοξενούμενοι της ομάδας Frown Tails, οι συντελεστές του Nauru Project θα επιχειρήσουν τη δραματοποίηση διαδικτυακών πληροφοριών που υπάρχουν στο blog, μέσω ατομικών tutorials.

Workshop

Σάββατο 24/9

To workshop επικεντρώνεται στην ανταλλαγή συνειρμών και τη συλλογή ευρημάτων. Mε αφετηρία το νησί του Nauru, oι συμμετέχοντες καλούνται να προσθέσουν στο project το προσωπικό τους διαδικτυακό μονοπάτι. RSVP to info@frowntails.com

Performance

Πέμπτη 29/9, Παρασκευή 30/9

Performers: Πολυξένη Σάββα & Θανάσης Πετρόπουλος

Από τις 17.00- 20.00 παρουσιάζονται προσωπικά tutorials. RSVP to info@frowntails.com

Open Performance: 20.30

Η Μαρία έχει συμμετάσχει σε ομαδικές εκθέσεις όπως: ‘I Do’, Six Dogs Project Space, Αθήνα, ‘Trace’, Sanhe Museum, Χανγκζού, Κίνα, ‘Meteor’, New Court Gallery, Ντάρμπισαϊρ, ‘Giatrakou 28’, ReMap KM 2, Αθήνα, ‘The Culture Industry: Folklore & Clichés’, VOX, Αθήνα, ‘VANM’, Slade Research Centre, Λονδίνο, ‘Urchin Eater’, Yinka Shonibare/Guest Projects, Λονδίνο, ‘Illumination’, Service Point Building, Μάντσεστερ, ‘Calypso’, Videotheque, Sala Rekalde, Μπιλμπάο, ‘Taenu’, Tactile Bosch, Κάρντιφ και ‘The Works of Others’, Whitechapel Library, Λονδίνο. Το 2010, η Γεωργούλα πήρε μέρος στα residencies ‘Kardamili Project’ στην Μάνη και ‘Utopia Project’ στο Ρέθυμνο, ενώ τον Μάρτιο του 2011 το βρετανικό περιοδικό ArtReview την συμπεριέλαβε στο ετήσιο αφιέρωμα ‘ArtReview Future Greats 2011’

Nauru Project, Maria Georgoula

The Nauru Project is an ongoing artists' collaboration based on the collection of information regarding the South Pacific island of Nauru, the world's smallest island nation.

The contributors of the Nauru Project will attempt to dramatise the multiple information of Nauru Project’s blog, via individual’s tutorials given to public and an open performance.

Workshop

Saturday 24/9

This workshop focuses the collection of digital findings related to Nauru island. The participants are invited to create their personal internet path.RSVP to info@frowntails.com

Performance

Thursday 29/9,Friday 30/9

Performers: Polixeni Savva & Thanasis Petropoulos

Book your personal slot from 17.00- 20.00 at info@frowntails.com

Open Performance: 20.30

Maria's selected group exhibitions include; ‘I Do’ at Six Dogs Project Space, Athens, ‘Trace’ at Sanhe Museum, China, ‘Meteor’ at New Court Gallery, Derbyshire, ‘Giatrakou 28’at ReMap KM 2, Athens, ‘The Culture Industry: Folklore & Clichés’ at VOX, Athens, ‘VANM’ at Slade Research Centre, London, ‘Urchin Eater’at Yinka Shonibare/Guest Projects, London, ‘Illumination’ at Service Point Building, Manchester, ‘Calypso’ at Videotheque, Sala Rekalde, Bilbao, ‘Taenu’ at Tactile Bosch, Cardiff and ‘The Works of Others’ at the Whitechapel Library, among others. During 2010, Georgoula took part in the ‘Kardamili Project’ residency in south Peloponnese and the ‘Utopia Project’ residency in Crete. In March 2011, Georgoula was included in ‘ArtReview Future Greats 2011’ the annual feature by the British magazine.

The Nauru Project @ Frown Tails ReMap 3

Nauruan Matt Alaeddine sets the world record for the Fattest Contorsionist

Photo: The World's Fattest Contorsionist, Matt Alaeddine shows one of his moves. Despite his mountainous size Matt Alaeddine can press the soles of his feet to his cheeks and do the 'sumo' splits. (enlarge photo)

The Guinness world record for the fattest nation was set by the island state of Nauru, where the average BMI is 35.

Mr Alaeddine's weight fluctuates between 400lb (28stone) and 450lbs (32stone) depending on the 'candy associated season'. 'Obesity! It's working for me,' he joked. He is part of the Jim Rose Circus that features extreme, often masochistic acts from sword swallowing to genital lifts. Alaeddine is one of three Edmontonians in the American troupe of pain-loving freaks. The roster also includes his friends Ryan Stock and Amber Lynn Walker of the Discovery Channel's Guinea Pig fame. When performing his contortions, Alaeddine stuffs his rolling hillsides into a gold nylon suit labelled "one size fits all" that he bought from the women's section of a hipster-friendly clothing store. 'You go to work every day sitting at a desk,' he told the Journal reporter. 'It's not for me. I mean, some people, they just want to get out there and climb and mountain...I'm not going to climb a mountain. Comedy is my mountain. Contortion is my mountain.'

The Empire of Atlantium

The Empire of Atlantium is a unique parallel sovereign state based in New South Wales, Australia.

Atlantium recognises that the days of nation-states founded on fixed geographical locations or majority ethnic identities are numbered, as global mobility, cultural evolution, and the growth of electronic communication networks render the assumptions that underlie and provide justification for their existence increasingly obsolete.

In an age where people increasingly are unified by common interests and purposes across - rather than within - traditional national boundaries Atlantium offers an alternative to the discriminatory historic practice of assigning nationality to individuals on the basis of accidents of birth or circumstance.

Atlantium has a heritage that spans three decades. What began as a local political statement by three Sydney teenagers on 3rd Decimus, 10500 (27th November, 1981) has since evolved into the world's foremost non-territorial global sovereignty movement and state entity, with a diverse, rapidly growing population living in some ninety countries.

Atlantium is predicated on a belief in the inevitability and the desirability of eventual global social, economic and political union, and it operates as a secular, pluralistic, liberal, social democratic republican monarchy. We encourage the active participation of Citizens in the public life of the Empire, and invite anyone with the desire and motivation to forge their own destiny as a true citizen of the world to consider joining us.

George II

Imperator et Primvs Inter Pares

Sovereign Head of State

Lilypad City - BBC News

It has pretty much become universally accepted that global warming is having an effect on global ocean levels. The effects of sea level rise are potentially devastating with millions of coastal and island inhabitants at risk of being displaced. For example, it is predicted that within 60 years the island nation of Kiribati, home to 90,000 people will be completely submerged beneath the sea.

In response to this potential devestation, engineers and scientists are attempting to come up with ways to support a growing population on less land. One of the more interesting proposals is known as “Lilypad.” Lilypad is a floating Ecopolis for climate change refugees.

Designed to house up to 50,000 people Lilypad travels the ocean currents from the equator to the poles following marine streams. Lilypad is a prototype of an auto-sufficient amphibious city. The city will feature green technologies such as solar, wind, tidal and biomass energy production. The double skin exterior of the city will be constructed of polyester fibres covered by a layer of titanium dioxide which reacts with UV rays to enable the absorbtion of atmospheric pollution.

No word on whether or if this type of floating city will ever be developed, but its sad that we have to consider developing these projects in order to preserve human survival.

For more information visit Vincent Callebaut Architects

http://www.vincent.callebaut.org/

Ουεσσάντ

Το μικρό βραχώδες νησί Ουεσσάντ λίγο πιο έξω απο τα παράλια της Βρετάνης, αποτελεί το πιο βορειοδυτικό σημείο της Γαλλίας. Εκτός των πολυάριθμων φάρων και ένος σπάνιου είδους μαύρου και ιδιαίτερα κοντού πρόβατου που φέρει το όνομα του νησιού, στο νησί Ουεσσάντ μπορεί κανείς να βρεί και μια βιβλιοθήκη αφιερωμένη αποκλειστικά στην νησιωτική λογοτεχνία.

Εκεί, ο σύλλογος CALI, σύλλογος για τον νησιωτικό πολιτισμό, την τέχνη και την λογοτεχνία, οργανώνει κάθε χρόνο διαγωνισμό για το καλύτερο λογοτεχνικό έργο με θέμα τα νησιά.

Τα Νησιά Όρκνι, Σκοτία

Οι Ορκάδες (Αγγλικά Orkney IPA ['ɔːkni], Σκωτικά Γαελικά Arcaibh[1][2]) είναι ένα αρχιπέλαγος το οποίο βρίσκεται κοντά στις βόρειες ακτές της Σκωτίας, από τις οποίες απέχει μόλις 16 χιλιόμετρα, και νότια από τα νησιά Σέτλαντ. Το αρχιπέλαγος αποτελείται από περίπου 70 νησιά, από τα οποία κατοικούνται τα 19.[3] Η συνολική έκταση των νησιών είναι περίπου 990 τ.χλμ. και ο πληθυσμός τους ανέρχεται στους 19.245 κατοίκους.[4] Το μεγαλύτερο νησί είναι το Μέινλαντ (The Mainland), το οποίο βρίσκεται στο κέντρο του συμπλέγματος και χωρίζει τα υπόλοιπα σε δύο ομάδες, τα βόρεια και τα νότια νησιά. Οι Ορκάδες ανήκουν πολιτικά στο Ηνωμένο Βασίλειο, ενώ διοικητικά αποτελούν την ομώνυμη περιφέρεια (Orkney Islands). Το Κέρκγουολ (Kirkwall) (8.686 κάτοικοι το 2006),[5] η μεγαλύτερη πόλη και διοικητικό κέντρο, βρίσκεται στο νησί Μέινλαντ. Το όνομα Ορκάδες μαρτυρείται από τον 1ο π.Χ. αιώνα ή και νωρίτερα, ενώ τα νησιά κατοικούνται εδώ και τουλάχιστον 8.500 χρόνια. Αρχικά κατοικήθηκαν από φυλές της Μεσολιθικής και της Νεολιθικής περιόδου και στη συνέχεια από τους Πίκτους. Το 875 οι Ορκάδες καταλήφθηκαν και προσαρτήθηκαν στη Νορβηγία και εποικίστηκαν από Νορβηγούς. Το 1472 εξαιτίας της αδυναμίας εκπλήρωσης της προικώας συμφωνίας τής Μαργαρίτας της Δανίας προς τον σύζυγό της Ιάκωβο Γ' της Σκωτίας, οι Ορκάδες προσαρτήθηκαν στοΒασίλειο της Σκωτίας.[6] Στις Ορκάδες βρίσκονται μερικοί από τους παλαιότερους και καλύτερα διατηρημένους αρχαιολογικούς χώρους της Ευρώπης. Ο Πυρήνας των Νεολιθικών Ορκάδων (Heart of Neolithic Orkney) στο νησί Μέινλαντ έχει χαρακτηριστεί ως Μνημείο Παγκόσμιας Πολιτιστικής Κληρονομιάς της UNESCO. Η υποκείμενη γεωλογική βάση όλων των νησιών αποτελείται από βραχώδεις σχηματισμούς από ερυθρό ψαμμίτη. Το κλίμα είναι ήπιο και η εύφορη γη καλλιεργείται κατά το μεγαλύτερο μέρος της. Η γεωργία αποτελεί τον σημαντικότερο τομέα της οικονομίας, ενώ η αξιοποίηση της αιολικής και της υδάτινης ενέργειας αποκτά ολοένα και μεγαλύτερη σημασία. Οι κάτοικοι των νησιών χρησιμοποιούν μια ιδιαίτερη διάλεκτο και διατηρούν την πλούσια λαογραφική τους παράδοση. Στα νησιά υπάρχει αφθονία άγριας πανίδας, πλούσιας σε θαλάσσια είδη και πτηνά.

Rabbit Island Artist Residency: The Story of a Remote Island in Lake Superior

Imagine a remote, forested island in the largest body of freshwater in the world. Now imagine living on that island and being a part of one of the most unique and challenging artist residencies in the world. Rabbit Island is that island, and with your help, Rabbit Island will become that residency.

LOCATION

Rabbit Island lies three miles east of Northern Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula on a gentle rise of sandstone which breaks the blue surface of Lake Superior. It is an undisturbed 90 acre island of forest and rock teeming with wildlife; a rugged, northern ecosystem that remains in its natural state, never in its history suffering development or subdivision.

In February 2010 Rob Gorski had the incredible opportunity to purchase the island (he found the ad on Craigslist!) and worked with the local nature conservancy to place an environmental easement on the land, ensuring that the ecosystem would remain protected forever.

With preservation locked in, the next step will be to create a space where artists and creative researchers can draw from this unique wilderness in their practices.

PROJECT NEEDS

The Rabbit Island project specifically revolves around building a solid (but modest) cabin for future residents to stay in and a studio for artists to work in. We plan to build these from the island’s own stone and wood.

With your support we’ll be able to get the supplies and materials to make this all a reality. Here are our main needs—

-Transportation to the island. This includes the very important boat! We plan on buying one second-hand from somebody in the local area so we’ll be able to access the island and transport materials there.

-Chainsaws and an Alaskan/portable saw-mill. The island is heavily forested and we want to create sustainably by using what is locally available. We’ve already worked with an arborist and forestry planner and will continue to work with them to develop a plan to select a small amount of trees from the island which will be processed into sustainably harvested, finished timber using the minimal tools that we have on site.

-Power tools and hand tools. To help during the initial construction these tools will remain in the residency for future artists-in-residence to use.

-Solar panel. To provide charging power for tools and other power needs during the building period and general power for the residency in the future.

ETHOS

Ecological concerns are a growing influence within the consciousness of society and the creative practices of many people. Visual artists, writers, designers, architects, farmers and creative researches of all types are doing some amazing things and we want develop an amazing space for those practices to flourish and be challenged. This artist residency presents some really unique constraints: It is off-the-grid, it is nature in its purist form, it’s an experiment, a laboratory. It is isolated from all centralized forms of transportation, energy production, food industry, and, the world of art. Rabbit Island represents a chance to creatively explore ideas related to the absence of civilization in a well-preserved microcosm.

This is why we want to establish an artist residency on Rabbit Island.

WHAT'S NEXT?

Andrew Ranville, a graduate of the Slade School of Fine Art in London, United Kingdom, will be the principal artist-in-residence and it will be his mission to design and construct these structures, incorporating them into the landscape of the island. He will draw from the experience of his current art practice as well as previous installations in wilderness settings in Europe and America.

Before coming to Kickstarter we’ve been hard at work– last summer Rob and a small team were able to setup a (mostly-completed) Adirondack shelter on the island to establish a home-base to branch from. But without the funds to go on things slowed down quickly. That is where we need you, the Kickstarter community. We are extremely motivated to continue working on the island and have a plan ready to go!

By supporting us you’ll receive our eternal gratitude and a Rabbit Island-specific token of our appreciation! Just take a look at the list on the right for what you’ll receive for your pledge. If you love the idea of Rabbit Island but are simply unable to support us with a monetary pledge at this time we would be grateful if you linked to us on Facebook or Twitter, etc.

If you are backing a physical goods reward from outside the US please add $10 to your pledge to accommodate overseas/international shipping costs. Thanks!

Thanks for reading, please spread the word! If you have any questions, ideas, cheers or jeers, please don’t hesitate to get in touch!

Sincerely,

Rob & Andrew

www.rabbit-island.org

www.robgorski.com

www.andrewranville.com

Islands and the Law: An Interview with Christina Duffy Burnett & Sina Najafi

CABINET MAGAZINE

Issue 38 Islands Summer 2010

Islands and the Law: An Interview with Christina Duffy Burnett

Sina Najafi and Christina Duffy Burnett

Bounded by water, circumscribed, and discrete, islands arguably constitute a natural geographical model for the classic territorial conception of a state (where sovereignty is thought to extend homogenously across a defined terrestrial region and terminate at the border). At the same time, the historical evolution of imperialism in both the East and the West has meant that most of the world’s actual islands became, at some point, off-shore colonial possessions of a distant metropolitan power. Treated as way stations, outposts, and resupply harbors, these outre-mer acquisitions tended to be spatially and legally marginal, regardless of their economic importance.

Christina Duffy Burnett is a professor of law at Columbia University, where she teaches legal history, immigration, citizenship, and the US Constitution. Much of her work deals with the legal problems that arise at the margins of empire. She spoke with Sina Najafi by phone in June of 2010.

This is a very general question, but let’s take a stab at it anyway: do islands matter in the law?

The best way to get at this may be to start with something quite specific. In the summer of 2003, I stumbled on a 969-page typescript treatise which is kept in the library of the US State Department. Flipping through this great leather-bound brick of onion-skin pages, I gradually absorbed that the whole massive volume had been put together in the 1930s by a lawyer working for the US Government who’d been given a killer assignment. Apparently somebody had walked over to the desk of this poor functionary, scribbling away in some basement office, and said something along the lines of: “You know, we have a bunch of islands in the Pacific and the Caribbean—little islands. How about you figure out what the deal is with all these places, legally speaking.” I was holding the result: The Sovereignty of Islands Claimed Under the Guano Act and of the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, Midway, and Wake. And it was splendid to behold: nearly a thousand pages of intricate legal arguments and historical documentation on the strange history of the United States’ nearly invisible, but surprisingly vast, insular empire.

The Guano Act? What is guano? It’s bat excrement, right?Yes. And bird doo, too. In this case, it refers to the bird version.

So there was a US law about bird droppings that somehow proves important for thinking about the law of sovereignty?Indeed. The Guano Islands Act of 1856 arguably laid the legal groundwork for American imperialism.

Can you explain how?Basically what happened was that in the first half of the nineteenth century, Europeans and Latin Americans figure out that the phosphate-rich deposits of seabird droppings that had accumulated on many small Pacific islands make spectacular fertilizer. The stuff is like magic, and farmers everywhere are suddenly clamoring to get their hands on some. There’s a boom, the price skyrockets, the Peruvians more or less control the market, and supplies are short. Everybody is looking for new sources, there’s tons of fake guano trading hands—it’s chaos. Enter the US farm lobby. Farmers in the United States start pressuring Congress to pass some sort of legislation that will improve domestic access to this vital excrement. The result is the Guano Islands Act, legislation that authorized the United States to take control of a guano island if a citizen discovered it and undertook certain actions to take possession of it.

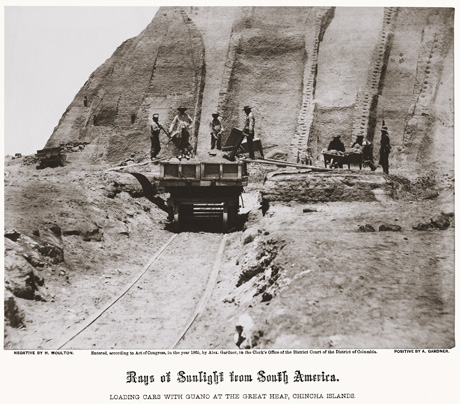

Hand-colored wood engraving from 1894 depicting guano being collected on one of Peru’s three Chincha islands in the mid-1870s. By this time, very little guano was left on the islands.

What was new about that? Hadn’t Americans been taking possession of new lands more or less since the Mayflower?

Right. In a way, yes. But in another way, not exactly. The history of US territorial expansion is actually very interesting, and not straightforward, legally speaking. As you know, initially there were those original thirteen colonies. But several of them also had “territories.” These were kind of their backlands to the west. When the newly independent states came together to form a union, and to write a constitution, they spent a certain amount of time trying to sort out how the territories were going to fit into the new nation. Hanging over all these negotiations was this broadly shared notion that the United States were destined to expand—indeed, that this emerging polity was likely, eventually, to extend across the continent. To be fair, not absolutely everybody was on board with this, but we are painting with a broad brush here. At any rate, the future of the territories eventually became clear: they were going to become states someday, once there was a proper population, sufficient political organization, etc. So the actual US Constitution contains precious little about the territories: basically there’s a clause stating that Congress will govern them, and another about their admission into statehood.

Is there a provision for acquiring new territories?Interestingly, no. And this famously worried Thomas Jefferson circa 1800 when the French government offered him something like a third of North America at a fire-sale price—what would eventually be called the Louisiana Purchase. Actually, it’s a great moment, because Jefferson—who tended to be very strict in his constitutional interpretation—even went so far as to draft a constitutional amendment empowering him to acquire new territories for the nation. But then he gets cold feet and sticks the draft in a drawer. About that time, he writes a fantastic letter to a friend about all this, and he says, basically, “Well, you know, the less said about the constitutional difficulties here the better.” Which is pretty much contrary to everything he ever said about the Constitution. Oops. That can happen when you become President.

That process of territorial acquisition continues throughout the nineteenth century. How is territorial expansion out to islands any different?The answer brings us back around to that thousand-page treatise sleeping in the bowels of the State Department. The key difference has to do withsovereignty. It turns out that there was quite a bit of debate around the passage of the Guano Islands Act. The whole thing made a few people pretty nervous. Was all this, they wondered, some sort of secret plot to start setting up overseas island colonies? There’s resistance to this notion in various quarters. So the bill’s main sponsors—to avoid controversy—go to great lengths to spell out that this business about “claiming” the islands is just about scooping up the guano, nothing more. The original draft of the legislation used the formal language of legal expansion—“territory,” “sovereignty,” and so on—but then, when the objections start, all that comes under a red pen. Out goes the word “territory,” which sounded too permanent, too much like the prelude to statehood. In comes a new word, “appertaining”—as in, these islands appertain to the United States as “possessions.”

And what does that mean, legally speaking?That’s the beauty of it. Nothing! Or, rather, no one had any idea. It was just a sort of a vague way of saying, “It’s, like, ours, pretty much.” The term “appertaining” had no previous usage in this context. At some point I even tried to sort out where the drafters of the bill got it from. As I recall, the term originated in property law as a way of talking about stuff that came attached to something else, like “the waters appertaining to the estate” or railway sidings that “appertained” to a railway, etc., etc. You can sort of see it drift from talking about the waters and other resources “appurtenant” to the guano islands, to being used to talk about the relationship between the islands themselves and the United States. It was basically a fudge. A way of taking the places as possessions, while being careful not to call themterritories, since that implied constitutional entanglements. It was a way of taking the places without really taking responsibility for them within the federal system. The bill also carefully removed the language of “sovereignty,” since that, too, seemed potentially to entail various obligations under domestic and international law. And finally, to get the bill to pass, they also stuck in a bit about how the United States could get rid of the places if it wanted—that there was no commitment to hang onto these islands after the resources had been stripped or their utility otherwise terminated.

And the act passes in that form?It does, and boom, there are all these wildcatters and roughnecks throwing up the Stars and Stripes on little mounds of manure all over the world. In the end, more than seventy such islands are actually secured under the act, and many more are claimed (unsuccessfully, for one reason or another). But that’s not the interesting part, really—although it’s curious enough, and there are some great stories about what goes down on these islands: shanghaiing Polynesian laborers, piracy (of course), mutiny, etc. Some of the islands are still claimed by various shady types. Indeed, a rather mysterious gentleman contacted me some years ago in connection with his alleged title to an uninhabited guano island in the Caribbean.

A James Bond villain-type?I don’t think I can speak any further on that matter over an unsecure line. Now, legally speaking, what’s significant about all this is that the act created a very important and new kind of place in the American legal system. A weird sort of non-place, from a constitutional perspective. These islands “belong” to the US, but they aren’t really a “part” of the United States. What law applies there? Not really so clear. What rights does an American citizen have on such an island? Again, not clear. In one sense, you might say, “Who cares? These are just some rocks out in the middle of nowhere,” but the deeper issue is that this move—withholding sovereignty—turns out to be a key aspect of the expansion of imperial power in the nineteenth century. And in certain disconcerting ways, we see the same move being made more recently in connection with the war on terror: extend power, but disclaim sovereignty—in order to retrench in terms of legal commitments.

Alexander Gardner, “Loading Cars with Guano at the Great Heap, Chincha Islands,” 1865. Spain, which did not recognize Peru’s independence until 1879, occupied the Chincha islands in April 1864 but lost the ensuing war. Courtesy Library of Congress.

So this is what you mean by saying that the Guano Islands Act established a significant aspect of the legal framework for American imperialism.

Right. We tend to think of empires in expansive terms, as projecting across space, but in fact, as far as the law is concerned, the projection of imperial power has frequently traded on the careful refusal to extend formal sovereignty, since this often comes with unpleasant obligations. European empires were especially good at all this: trust territories, informal control, etc. You didn’t want to go out and claim sovereignty over all these messy places. From a legal perspective, that would be a total pain!

But given that the US is born in an anti-colonial revolution, or so Americans like to tell themselves, there must have been resistance to modeling American legal structures on those of, say, the British Empire.Some, sure. But it is also the case that the United States does very much have its imperial meridian, a moment when it embraces the ideal of a global colonial empire. This is 1898, of course—the Spanish-American War. The US flexes its muscle, crushing an Old World power, and winning, in the process, a mess of islands: the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. For a while there is a sort of Iraq-style situation in Cuba, too: the US has “liberated” the place, but occupies it, claiming it needs to be “pacified”; US officials insist they want to leave, but don’t. Complicated. In the end, we micromanage their writing of a constitution, and then formally leave, except, of course, for Guantánamo, which we keep.

A legally ambiguous place, for sure.Indeed, but the whole episode raised vexing constitutional problems from the get-go. Suddenly the US has all these new insular possessions overseas—the spoils of war. And once again, the question is: What’s the status of these places, legally speaking? Are they “territories” in the constitutional sense? They have to be, because that is the only way, under the US Constitution, that Congress can be authorized to govern them. This hadn’t really been an issue on the guano islands, since they had no “governments.”

What about the guys with guns?Right. There were always the guys with guns. But they tended to be freelance despots, overseers, cowboys with ships—pirate-types. With a few corporations in the mix. None of them focused on governance issues per se. They focused on resource extraction. So 1898 raises new problems. In fact, the acquisition of all these islands circa 1900 leads to something close to a constitutional crisis. If they are territories, then are they going to becomestates? But they are full of hot-blooded, swarthy types! The eugenicists, among others, don’t like it. At the same time, the US Constitution makes no provision for an American empire—for federal “dominion” over peripheral colonies not intended for statehood. All the lawyers are busy reading up on how England and France run their imperial systems, and there are various proposals for how to tweak things in the US to make it all work. In the end, the issues are resolved in a set of Supreme Court decisions handed down in the first decades of the twentieth century, known collectively as the Insular Cases—since they were the cases that determined how the US would deal with all these islands.

So what happened?Once again, islands serve as the site for legal experimentation and for some questionable legal innovations. It’s clearly unacceptable to a majority of Americans to contemplate these new acquisitions as “really” part of the United States—as in, on the way to statehood. But at the same time, no one wants to just give them away. What about the White Man’s Burden and everything? Kipling actually wrote that poem for this very occasion—to try to get the Americans to strap it on as imperialists. In the end, the court finesses it, and the justices conjure up a distinction between two kinds of US territory: “incorporated” (meaning “en route to statehood,” i.e., “containing a good number of Caucasian Protestants with acceptable table manners”) and “unincorporated” (meaning, more or less, “the US is in charge here”). The latter category was basically invented to give constitutional blessing to the US directly governing a network of colonial islands around the world: they were “unincorporated territories.” In an international sense, they were part of the US, but they weren’t really “the US,” if you know what I mean. One legal opinion described the relationship this way: these islands were “foreign to the United States in a domestic sense.” Got that? The Supreme Court resurrects the language of “appertaining,” too: it says these places are not “part” of the United States, but merely “appurtenant” to it. Meaning what? Well, they’re “ours,” but not “us.”

Wreckage on Palmyra. The plane, carrying seven radio operators, veered off the island’s sole runway as it tried to land on 5 January 1980. Courtesy Laura Beauregard / US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Does the US still have “territories”? Does the incorporated/unincorporated distinction still exist? If so, what significance does it have?

It does. The best way to get at this may again be to zero in on a very particular and legally anomalous island—or, in this case, archipelago—called Palmyra. Palmyra is basically in the middle of the Pacific, slightly south of Hawaii. There’s pretty much nobody there—some sort of caretaker, a few biologists. Anyway, it’s a bunch of little islets, very remote. Nevertheless, this place has the distinction of being the United States’ unique “incorporated” territory. Which is to say, it is not a state, or a part of a state, but it is a “part” of the United States in a fundamental way.

Meaning what, exactly?Well, people have argued a great deal about what the distinction between incorporated and unincorporated actually meant, legally speaking. In Puerto Rico, where I am from, this issue is positively explosive, since the island was one of those places designated as an unincorporated territory after the Spanish-American War. In fact, I would argue that it remains an unincorporated territory, but those are fighting words on the island—let’s not get into it. Where territorial status is concerned, the basic issue has traditionally been understood to be: “Does the Constitution follow the flag?” Which is to say, if a place belongs to the US, does the Constitution apply there automatically—all the rights and protections it guarantees, etc.? The traditional story has gone like this: the Insular Cases, by making the distinction between incorporated and unincorporated territories, answered this question in the negative. No, just because we hoist the flag does not mean that all these dark people are suddenly entitled to equal protection, jury trials, and all that other good stuff. That stuff is only for theincorporated territories—as they make their way to statehood. With the unincorporated ones, the Constitution, it has been said, “doesn’t apply.” This sort of thing gets pretty hairy as a legal argument, and I do not want to get bogged down in a lot of technical stuff. Suffice it to say that figuring out what constitutional protections apply to what offshore islands has been—and remains!—a very difficult and important legal problem for the United States. As it happens, my own view is that the most important issue at stake in the incorporated/unincorporated distinction is, in fact, the issue of permanence. I’ve argued for some years that the thing that made everyone most nervous about the new insular possessions at the end of the nineteenth century was the idea that the US would be stuck with them forever. You have to remember that the Civil War was still very fresh in people’s minds in that period. And what was the issue there? It was Lincoln’s central claim that hecould not accept the secession of the southern states—not even if he wanted to. He asserted that the Constitution did not permit a withdrawal of a part of the union. This was a situation where constitutional interpretation was performed in blood. I believe that the United States’ imperial exuberance was haunted by this issue: What would happen if, later, there was a need to alienate these places—to get rid of them? Would this trigger a constitutional crisis? At its heart, the distinction between incorporated and unincorporated territories was a distinction between permanence and fungibility. The insular cases in effect smuggled a theory of secession into American law.

So do you foresee a civil war breaking out over Palmyra?I think we’re in the clear there. My impression is that the Nature Conservancy is basically running the place these days. Very friendly people, I am sure. But I do think that, absurd as it may sound, there is a perfectly credible constitutional argument that, in view of Palmyra’s “incorporation,” the place forms an integral part of this indestructible union, and that, say, if the US wanted to cede it to Kiribati, there would need to be a constitutional amendment.

Can you explain how Palmyra ended up in this weird position?It was originally claimed as a guano island, under the 1856 act. Then it turns out there is no guano, so it’s abandoned. Eventually the Kingdom of Hawaii takes it, then we take Hawaii. Hawaii is deemed to have been formally “incorporated” into the United States circa 1900, and set on the road to statehood, but when statehood actually happens, the Palmyra chain isn’t on the map. I’m not really clear on why, but the archipelago of Palmyra ends up an orphan in legal terms.

But if it was incorporated, then is it now on its way to statehood?That’s what I’m pulling for. You and I can be the senators. I mean, in some sense you are pointing to a kind of reductio ad absurdum of legal boundary drawing, which is fair enough, and, indeed, what I take to be striking about the Palmyra story is exactly the way it exemplifies the role of legal boundary drawing in the history of imperialism. Empires work by extending power and people, configuring concentric spheres of protection and influence—all of this is about sliding boundaries. Palmyra sits out there in the Pacific sun as a monument to all the boundary tweaking that has gone on at the periphery of an expansive American experiment.

Let’s fast-forward for a moment. I know that the Supreme Court has cited your work on the Insular Cases in connection with recent litigation on Guantánamo. Can you talk for a moment about this island outpost and its liminal legal status?Well, again, here the issue has been one of legal boundaries. Guantánamo is not a “territory” of the US in any of the senses we have been talking about. It is a strange sort of lease—a perpetual lease, the terms of which specify that the arrangement cannot be altered without the mutual consent of Cuba and the US. This is not the sort of lease that happens absent considerable pressure, and indeed the arrangement—very humiliating and annoying to Cubans—was a precondition of the withdrawal of US occupying forces after the Spanish-American War. The US wanted it as a naval base. This was the era of Alfred Thayer Mahan—The Influence of Sea Power on History (1890). Everybody needed coaling stations all over the world. Control over the oceans was the geostrategic obsession of the great powers. Much of the imperial island craze of the turn of the century is about this. Anyway, it is this odd status—the US is definitely in charge, but the place is, nominally anyway, part of Cuba—that facilitated the creative legal work by the Bush administration lawyers. In essence, they argued that the protections of the US Constitution were irrelevant to what went on there, since the US wasn’t the sovereign.

So who is? Castro?Basically. That was sort of their argument. Just to be clear, this stuff is also very complicated, because there are all sorts of special legal considerations when you are talking about military bases, and so on. But grossly speaking, you are dealing with another legal no-man’s-land, another island put forward as beyond the constitutional pale. Significantly, of course, the Supreme Court has been chipping away at this posture. The Boumediene case in 2008 marked an important moment, because there the Court rejected the idea that the prisoners being held at Guantánamo were beyond the reach of some of the basic legal protections of the US system.

Maybe the CIA needs to call your James Bond villain friend.You know, you say that, and I have to admit that when all of this first started going down—reports of secret prisons, extraordinary renditions, etc.—the first thing that occurred to me was that someone should be checking to see what was up on the seven guano islands that the US still holds. They were, in a way, the original law-free zones, and they are still out there. I think one or two might even have an airstrip.

Christina Duffy Burnett is an associate professor of law at Columbia University. She is the co-editor of Foreign in a Domestic Sense: Puerto Rico, American Expansion, and the Constitution (Duke University Press, 2001) and the author of numerous articles and essays on the law, history, and politics of American empire.

Sina Najafi is editor-in-chief of Cabinet.